2. Need and Opportunity

A little context

A little context

The citizen experience is broken. The design of our public institutions continue to reflect their 18th and 19th Century origins. Public administration remains an unattractive career path for creative, entrepreneurial-minded college graduates. And as the world changes at an increasingly faster rate, our systems for collective decision-making have failed to keep up.

As California's capital, the Sacramento region is the locus of power for one of the most influential states in the most powerful country on Earth. This, however, is not without its consequences. Political gridlock, confusing bureaucracies, and program mismanagement do not occur in a vacuum. Because the proportion of our workforce that comprises the public sector is nearly double the state average, attitudes toward government inhibit our region’s economic competitiveness.

Even worse, nearly every major attempt to “fix the system” has failed to deliver results. With an overreliance on political leadership and technocratic policy design, reform efforts either lack sufficient political support, collapse on their own weight, or do not address the root causes of governmental dysfunction. Of course, this track record largely pertains to the federal and state levels of government.

At the local level, new models of co-creation are laying a foundation of civic infrastructure needed to enable faster problem solving and greater social cohesion. Whether it’s volunteerism, civic hacking, or tactical urbanism, many citizens have come full circle and reached the conclusion that the best way to ensure a problem gets fixed is to fix it themselves.

Discussions about job creation and investment largely overlook the need to innovate within the public sector. Rather, public agencies—including our universities, healthcare institutions, and local governments—are positioned as tools for accelerating private investment. While this is a laudable goal, a different set of strategies and tactics must be developed to leverage the value creation potential within the civic space itself.

Next Economy—a high profile regional economic development initiative led by the Sacramento Metro Chamber, the Sacramento Area Commerce and Trade Organization (SACTO), the Sacramento Area Regional Technology Alliance (SARTA) and Valley Vision—prioritizes the following five goals to increase investment and create jobs (Next Economy, 2013):

With regard to the third goal, diversifying the economy, the Next Economy plan notes:

"According to recent U.S. employment statistics, the Capital Region’s government workforce is one of the largest per capita of any metropolitan region in the United States. Government has been a valuable contributor to the Region’s economy and there is little question that the presence of government has dampened the effects of past economic downturns. In the face of current economic and financial realities, however, forecasts call for flat to negative employment in the government sector for the foreseeable future (28)."

Even an optimistic outlook means that one-in-four residents will work in the public sector ten years from now (today, it’s almost one-in-three). The California Legislature literally would need to relocate the state capital to another region in order to make a meaningful dent in our share of public sector employment. Fostering a strong innovation environment must include changing the culture of government.

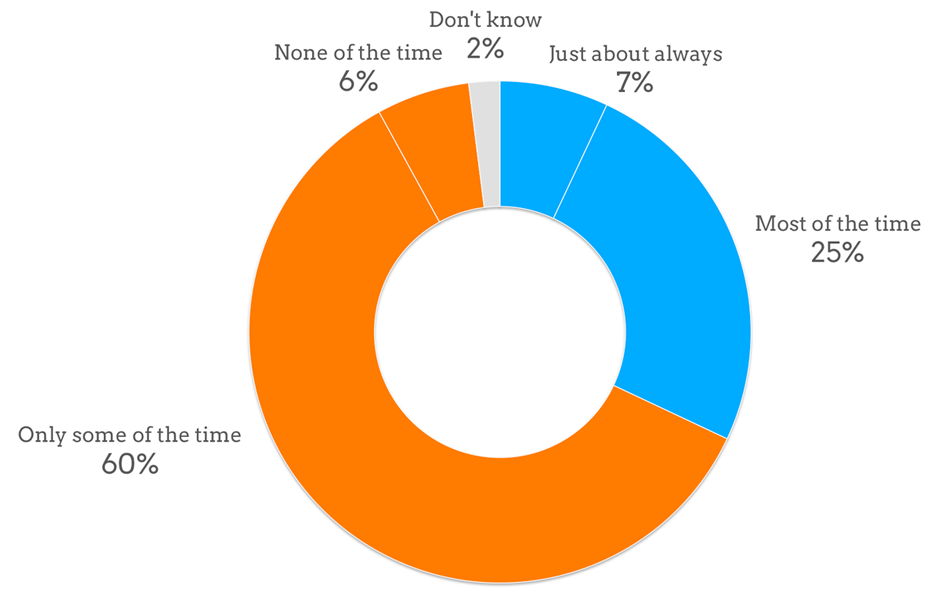

So what’s the state of trust in government? Although trust is greatest at the local level—where it's closest to the people, distrust in state government has a negative impact on how the Capital region is perceived. Earlier this year, the Public Policy Institute of California (2013) asked the following question to Californians in their Statewide Survey:

“How much of the time do you think you can trust the state government in Sacramento to do what is right—just about always, most of the time, or only some of the time?”

When it comes to government performance, we consistently accept the fact that public agencies are laggards in adopting new ideas. We just expect that government is not capable of keeping up with the pace at which the rest of the world is changing, much less do we believe that government could lead the way in the development of breakthrough innovations.

And yet, we live in an era of disruption. When legacy companies fail to adapt their business models to new market conditions, startups can enter the marketplace and not only cannibalize market share faster than at any other point in history, but create new value networks and markets in the process. This is known as disruptive innovation.

According to Harvard Professor and former Mayor of Indianapolis, Stephen Goldsmith (2010):

"With a structure designed for a simpler time, government has become ill-equipped to handle the complex task of solving our increasingly intractable social challenges. Even more fundamentally, though, government now must deliver its assistance not through traditional rule-bound hierarchical programs but through effective civic entrepreneurs operating in dense social and community networks (xxvi)."

The same trends we're seeing in the tech sector are just beginning to impact the public sector because our expectations are changing.

To guard against misuse of public funds, reformers of the early 20th Century brought in a new wave of rules and systems that restrict how resources could be allocated. In addition to strict accounting principles, disclosure and transparency were believed to be the best way of protecting against abuses. In former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis’ words,“If the broad light of day could be let in upon men’s actions, it would purify them as the sun disinfects.”

Bureaucracies serve an important purpose by enabling accountability. But accountability for what? Rules, hierarchy, and specialization are input-driven features to efficiently allocate decision-making and responsibility. For example, if fiscal mismanagement occurs, bureaucratic structures allow political leaders to assign blame. In fact, it was Woodrow Wilson—the father of public administration—who first proposed separating politics from administration to protect the public trust from abuses. Similarly, Frederick Taylor’s principles of scientific management assumed that every process has a single, optimal method.

Today, we know that bureaucracy comes with a significant tradeoff in the context of organizational culture. According to scholar James Q. Wilson (1989):

"Every organization has a culture, that is, a persistent, patterned way of thinking about the central tasks of and human relationships within an organization. Culture is to an organization what personality is to an individual. Like human culture generally, it is passed on from one generation to the next. It changes slowly, if at all (91)."

Bureaucracy dehumanizes organizations and the people who work in them. Yet, culture is a paramount concern among leaders in today’s most prominent companies. But can a more human organizational culture be an antidote to bureaucracy?

“It is true that bureaucracies prefer the present to the future, the known to the unknown, and the dominant mission to rival missions; many agencies in fact are skeptical of things that were “NIH”–Not Invented Here. Every social grouping, whether a neighborhood, a nation, or an organization acquires a culture; changing that culture is like moving a cemetery: it is always difficult and some believe it is sacrilegious (Wilson, 368).”

But Goldsmith argues that culture is not so immutable:

“So how might community leaders open up space for breakthrough civic accomplishments? They can do so by promoting a culture of innovation, providing information and forcing transparency, sponsoring events that create opportunities for social discoveries, and offering protection for those whose efforts, whether successful or not, challenge the status quo (74).”

He further articulates the role of civic entrepreneurs:

“Civic progress requires that those who advocate for new interventions build a community of engaged citizens with the power to demand change in social-political systems. This is true whether the barriers come from iron triangles, bureaucrats, unions, or incumbent providers. Civic entrepreneurs enter the social realm to make a difference—to perform—and their passion and talent are often distinct from the legitimacy enjoyed by incumbent providers or the political support enjoyed by the well connected (140).”

We can't wait for a change in culture to happen from within the system. Instead, we need to create a positive disruption from the outside.

Public Innovation has performed considerable research on current efforts to catalyze public sector innovation. The variety of approaches include both internal efforts within public agencies and efforts aided by outside organizations.

There are at least a dozen chief innovation officers working at the municipal level in the United States. This relatively new position spans a range of primary responsibilities from economic development to civic engagement, to open data and civic technology, and includes cities such as:

Some states, including Maryland and Massachusetts, also have chief innovation officers with statewide responsibility. These offices of innovation are often an important first step in setting the tone for a more permissive authorizing environment in which an innovation agenda may be pursued.

Boston, in 2010, and Philadelphia, in 2012, each opened a Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics (MONUM). The MONUM approach is focused on transforming service delivery through civic innovation. Although this model is a part of local government, these incubators provide a safe space for experimentation, along with the co-creation and co-production of public services with citizens—not just for citizens. Similarly, the MONUM model relies on partnerships with outside organizations and entrepreneurs, which in recent months has led to the emergence of a new term, civic fusion.

Code for America (CfA) helps governments work better by supporting the development of user interfaces that are simple, beautiful, and easy-to-use. The organization currently operates four programs:

The contribution to the civic innovation ecosystem that Code for America has contributed cannot be overstated. As a leading organization in this space, Code for America has been instrumental in connecting the dots across what might otherwise be disparate silos of activity occurring nationally. Most importantly, Code for America has tactfully shown a way for technology projects to change the culture of government by focusing on people and process issues.

San Francisco Citizens Initiative for Technology and Innovation (sf.citi) is a 501(c)(6) organization that builds civic technology and engages in public policy development. Backed by companies such as Twitter, Salesforce, Adobe, AT&T, and Google, Mayor Ed Lee refers to sf.citi as San Francisco’s “tech chamber of commerce.” As an outside organization, sf.citi has considerable flexibility in the projects it chooses to pursue and the means by which it pursues them. The organization has helped build apps to better manage public transit operations and police reports.

In 2009, the Smart Chicago Collaborative was born out of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to support the development of broadband infrastructure in Chicago. With the support of partners such as the City of Chicago, the MacArthur Foundation, and The Chicago Community Trust, Smart Chicago today is Chicago’s “new center of gravity for civic investments.” Today the organization supports developers building civic apps by providing free hosting and pursues new approaches, such as the Civic User Testing Group–which engages citizens to test the usability of civic apps to ensure that technology effectively addresses unmet community needs.

Sacramento region is making progress in public sector innovation. Of particular note, the Sacramento Area Council of Government’s Shared Services Task Force has focused on ways to collaborate toward more cost effective public services across city and county borders. This type of interagency collaboration is exactly what’s needed to change the culture of government and encourage public officials to break out of traditionally comfortable silos. Similarly, Davis and Sacramento have new innovation offices that are well-positioned to initiate new projects with creative approaches to solving public problems. Through Mayor Christopher Cabaldon's forward-looking leadership, the City of West Sacramento recently became the first city in our region to establish an open data policy and the fledgling Code for Sacramento has successfully built a community of civic technologists. Yet, keeping up with the progress of other cities headed is not going to make us a global leader.

The Capital Region can and should distinguish itself in this space by leveraging its unique assets and collaborating with Public Innovation.

To truly innovate, the region needs the full weight of an entity committed to developing a robust civic innovation and social entrepreneurship ecosystem that will bring about the positive, yet disruptive, transformation to our civic culture. To be successful, however, Public Innovation will need to overcome the following barriers:

The time is now. This business plan is based on models that are already working in leading cities across the country. We not only have the ability to join the larger community of civic innovators and social entrepreneurs, but the opportunity to break new ground in this space. Several characteristics of our approach are distinguishable:

Georges, Glynne-Burke, and McGrath (2013) prescribe the following strategies for supporting civic and social innovators:

Strategy 1: Build Collective Capacity for Innovation

Strategy 2: Rethink Policy to Open Space for Innovation

Strategy #3: Develop a Culture of Innovation

Over the past year, Public Innovation’s model for impact has evolved from one that was largely focused on public sector innovation—within the confines of public agencies—to a more holistic model that addresses civic innovation at a systems level. Our current model integrates not just the roles of public servants, but also calls on leaders within nonprofits, the business community, and among everyday citizens to be part of a co-creative process to transform our civic culture.

To date, we’ve held six CivicMeet Sacramento meetups, launched Code for Sacramento, participated in several hackathons, facilitated a course on social innovation, co-sponsored a design workshop with leaders from Google, attended the Mayors Innovation Summit in Philadelphia, and engaged hundreds of Sacramentans in the process. Additionally, we’ve recruited an A-list of advisors from myriad sectors. The past year also has allowed us to experiment and determine which strategies will and will not work. For example, our renewed focus on citizen engagement is not only important for fostering the exchange of ideas among diverse perspectives, but also to create an environment where citizens are more tolerant of safe risk-taking by their public officials. Creating this external “authorizing environment” proved to be more feasible than going directly into public agencies and creating change from within.

Most importantly, we were able to successfully identify a key source of earned income: civic technology. As originally envisioned, Public Innovation would act as a traditional nonprofit and heavily rely on grant-funded projects to sustain ourselves. However, approximately six months into our existence, we discovered a large demand for technology solutions among public agencies and nonprofits. Although government procurement remains a challenge for us, we project that civic technology projects will provide us with 85 percent of our revenues by our fourth year of operation. Being fortunate enough to have such a substantial portion of earned income, our future fiscal health is promising.